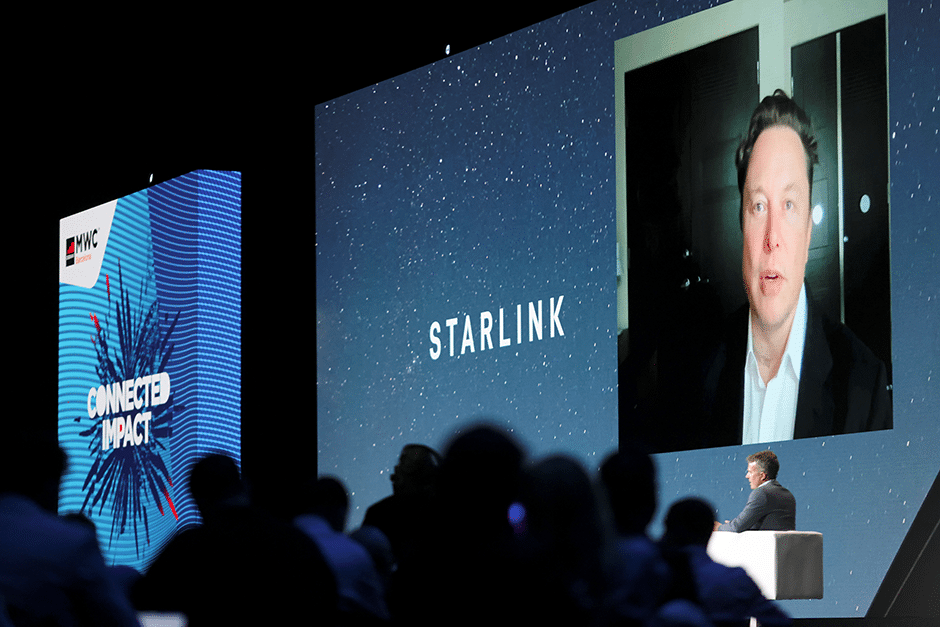

Starlink’s technology has the potential to connect parts of rural Minnesota where high-speed internet is expensive to build and hard to come by, but the service has also stirred up plenty of debate — and frustration — among public officials.

By Walker Orenstein | Staff Writer MINNPOST

When Kati Stage moved from the Twin Cities to Embarrass in rural northern Minnesota last summer, her only choice for the internet was HughesNet, a satellite service she said was slow “since day one.”

Then, in November, she one day noticed a “strange long line of lights” pass above her in the sky. After some Googling, she found out what it was: Starlink.

The service, owned by Elon Musk’s rocket company SpaceX, offers broadband through a growing network of low-orbiting satellites, which now number more than 1,700 and can look like a string of lights as they move.

The sign from above-led Stage to sign up for Starlink internet, and she said she loves the service, which she uses for work and entertainment. “We paid Hughes off and sent their modem back immediately after seeing the difference,” Stage said.

Experts say Starlink’s novel technology has the potential to connect swaths of rural Minnesota where high-speed internet is expensive to build and hard to come by. It’s heralded by some as practically a silver bullet for broadband woes in the state.

But Starlink has also stirred up plenty of debate — and even frustration — among Minnesota officials, who at times see the company as something of a distraction from efforts to publicly fund more traditional types of broadband such as fiber-optic cables.

“Starlink is kind of the shiny new penny that’s dangling,” said Michelle Marotzke, an economic development official with the Mid-Minnesota Development Commission in Willmar. “A lot of people ask about it: ‘Well, what about Starlink? That’s going to fix all of our problems.’”

Why Starlink is different

There are parts of Minnesota where people still don’t have access to quality broadband.

As of October 2020, 16.9 percent of state residents in rural areas did not have access to internet with download speeds of 25 megabits per second (Mbps) and upload speeds of 3 Mbps. The state has a goal to provide 25/3 Mbps access to everyone in Minnesota by 2022.

Peter Peterson, a computer science professor at the University of Minnesota Duluth, said high-speed internet has primarily come through cable television infrastructure since the 1990s, and that cable equipment wasn’t built in many rural areas largely because it is more costly to bury cable in sparsely populated areas with fewer potential customers to recoup costs. Public subsidies created a nationwide telephone network, but phone lines don’t have the same capacity for speedy broadband, Peterson said.

The state has lately subsidized construction of broadband infrastructure, namely fiber-optic cable, spending more than $126 million on a grant program for developers since 2014 before lawmakers approved another $70 million earlier this year as part of Minnesota’s latest two-year budget.

Fiber is reliable and fast, but it is also expensive to build, and other technologies have become more popular lately, too, including fixed wireless, in which homes get service from a signal placed high on a nearby building. There’s also traditional satellite internet.

Peterson said both can work well but have downsides. Fixed wireless needs some infrastructure, plus homes must be somewhat close to it and have topography that doesn’t block the signal. Satellite internet is expensive, and the service is typically slowed after hitting a data cap, Peterson said. It also has high “latency,” which is what creates, say, a delay in a video call between when you say something and when another person on the call hears it.

Starlink also relies on satellites, but it’s very different from traditional satellite internet. Typical connections rely on one large satellite. Peterson said that the satellite is roughly 22,000 miles in space and is in “geostationary orbit,” meaning it’s over the same spot on Earth at all times. SpaceX, however, has built a “constellation” of smaller, moving satellites that it launches from rockets into “low-earth orbit,” roughly 340 miles in the air, Peterson said.

“As long as there’s a satellite over your house at one time you can have internet service from this satellite,” Peterson said. “The latency is a lot lower because it’s so much closer and the bandwidth is really high presumably because they have enough hardware to support high bandwidth.”

On its website, Starlink says its broadband service is ideal for rural and remote communities and runs “without the bounds of traditional ground infrastructure.” Service is not available everywhere, but the company says it plans to “continue expansion to near-global coverage of the populated world.”

Starlink says users can expect to see download speeds between 100-to-200 Mbps. As the company launches more satellites and installs more “ground stations” — which are needed to provide the internet service to users — Starlink promises speed and latency will improve.

Starlink hasn’t imposed any data caps for now, and the service has cost $99 per month after an initial $499 for the internet receiver and other equipment.

The rocket company turned internet provider has many fans in Minnesota, including state Rep. Pat Garofalo, a Farmington Republican who previously chaired a House committee with oversight of broadband subsidies.

Garofalo said the state has been too reliant on paying for expensive fiber to expand broadband access in Minnesota. That may work for dense areas, but fixed wireless and satellite internet are better in sparser places, and are becoming more widely available regardless of whether they’re being subsidized, he said.

“This is just another example of technology solving our problems for us,” Garofalo said. “When they’re talking about making sure that communities have access, well everyone already does have access. The infrastructure is already in place, it’s just the monthly fees.

“Rather than subsidizing a fiber connection to a wealthy suburbanite who has a cabin in northern Minnesota, put some means-testing onto some Starlink annual plans,” Garofalo said. “That way you’re going to get more people more access to broadband at a lower price.”

Not a ‘silver bullet’

Starlink has been controversial, however, among some public officials who are trying to build broadband in rural areas of Minnesota. At a Minnesota conference dedicated to expansion of high-speed internet earlier this month, the comment section of one Zoom meeting morphed into something of a public airing of frustrations about the SpaceX service.

One person who chimed in was Lezlie Sauter, the economic development coordinator at Pine County in east-central Minnesota. While the Legislature and some local governments have consistently funded broadband grants used on fiber in recent years, Sauter said in a later interview that some people are dismissive of her efforts to expand fiber broadband in the area with public money “because they’re like ‘Starlink will fix it all, I don’t know why we’re even talking about putting fiber in the ground.’ ”

Starlink could be the only option for some people, but she said it’s not affordable for many while and fiber internet is reliable, fast and “almost fail proof” since it’s in the ground. Pine County residents have among the worst access to quality broadband in the state.

Marotzke, from the Willmar-based Mid-Minnesota Development Commission, said Starlink poses other concerns. Problems may not be able to be fixed as easily as traditional infrastructure, where someone can call a provider like an electric cooperative and have a technician show up at their house.

Starlink’s internet can still be slowed by inclement weather and obstacles like trees, and Marotzke said ongoing costs associated with thousands of satellites could prove to be expensive compared to fiber that requires little maintenance once it’s buried. “We have technology that is proven, that is solid,” Marotzke said. “We can literally put the shovel in the ground and get it done.”

Peterson, the UMD professor, also expressed doubts about Starlink being a broad solution to internet problems long term. SpaceX has to keep launching satellites as it gains customers, raising environmental “space junk” concerns and affecting astronomy. (Starlink has previously said it hopes to launch 42,000 satellites.)

Rural America also shouldn’t be forced to rely on one company, Peterson said, because if there are issues or outages that could affect a massive number of people. But if another competitor comes along, he said that would only grow the huge constellation of satellites.

One common argument among fiber proponents is also that it can be done now, while Starlink isn’t widely available yet. “We’re already behind,” said Jay Trusty, who chairs the Minnesota Rural Broadband Coalition, which includes telecom companies, counties, economic development officials and even the Mayo Clinic.

During the pandemic, Trusty said, “we had all these kids that couldn’t access their schools, people stayed at home trying to work from home.”

“We’ve got broadband issues that aren’t going to wait five, 10, 15 years.”

A growing presence in Minnesota

It’s unclear how many Minnesota customers Starlink has. That data is submitted to the state Public Utilities Commission but is considered a “trade secret” and not made public by the agency. A spokeswoman for SpaceX also didn’t respond to a request for comment. Still, the service is generally growing and becoming a larger part of Minnesota’s broadband universe.

SpaceX even won $8.42 million from the federal government to help subsidize broadband development in Minnesota late last year as part of a $9.2 billion grant program run by the Federal Communications Commission.

The grant program, known as the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF), included $408 million for Minnesota. SpaceX won bids to serve 7,529 customers — the second-most in the state of those participating in that round of the grant program.

A map of FCC grant winners shows SpaceX plans, at least preliminarily, to serve several rural pockets of Lake County and small parts of many counties, including Itasca, Koochiching, Crow Wing, Cass, Hennepin, Anoka and Clearwater. (Though it’s technically in Michigan, Starlink even won a bid to serve parts of Isle Royale, a remote island near the North Shore of Lake Superior.)

The FCC said at the time that nearly all locations to be served with help from the federal grants would get broadband speeds of at least 100/20 Mbps, and more than 85 percent would get gigabit speeds. Starlink has to offer broadband to at least 40 percent of locations in its RDOF zones by the end of 2024 and 100 percent by the end of 2027.

This summer, Starlink was approved by Minnesota’s Public Utilities Commission as an “Eligible Telecommunications Carrier” as part of the RDOF program. The commissioners, however, said in an order that because of the “novelty of Starlink’s proposal to provide “space-based” broadband,” the company needed to explain the benefits and services Minnesota customers in the grant areas would get that’s different from what customers outside the subsidy zones will receive.

In a June filing with the PUC, Starlink attorney Gregory Merz said the company has to offer Lifeline — a subsidy for low-income people — to qualified customers. FCC money will also allow Starlink “to accelerate service for those who need it most and prioritize deployment to the underserved” in RDOF areas.

That includes speeding production of satellites and customer equipment, and, despite the company’s claim of being a good fit for sparsely populated rural areas, Merz said federal cash makes it more cost-effective for Starlink to build the ground infrastructure it does need to serve thinly populated areas where it might not otherwise be financially worth it. “The same market forces that drive the placement of these (Starlink) gateways also drive the deployment of terrestrial networks,” Merz wrote.

Despite their concerns, public officials skeptical of Starlink said it could still be a good option for many Minnesotans. Sauter, from Pine County, signed up for the service roughly eight months ago, though she said she has yet to receive equipment.

Peterson, the UMD professor, said his only option in Lakewood Township north of Duluth is brutally slow DSL. And while he hopes his area can get grant money to start a fiber cooperative as a long-term solution, for now he also applied for Starlink and is on a waiting list. “I’m signed up for it because we don’t have fiber in our neighborhood,” Peterson said.